ÉTUDES OF PARIS

2024 (work in progress)

video (15 min)

Do we travel the world in search of authenticity, only to find ourselves reflected in the things we already know?

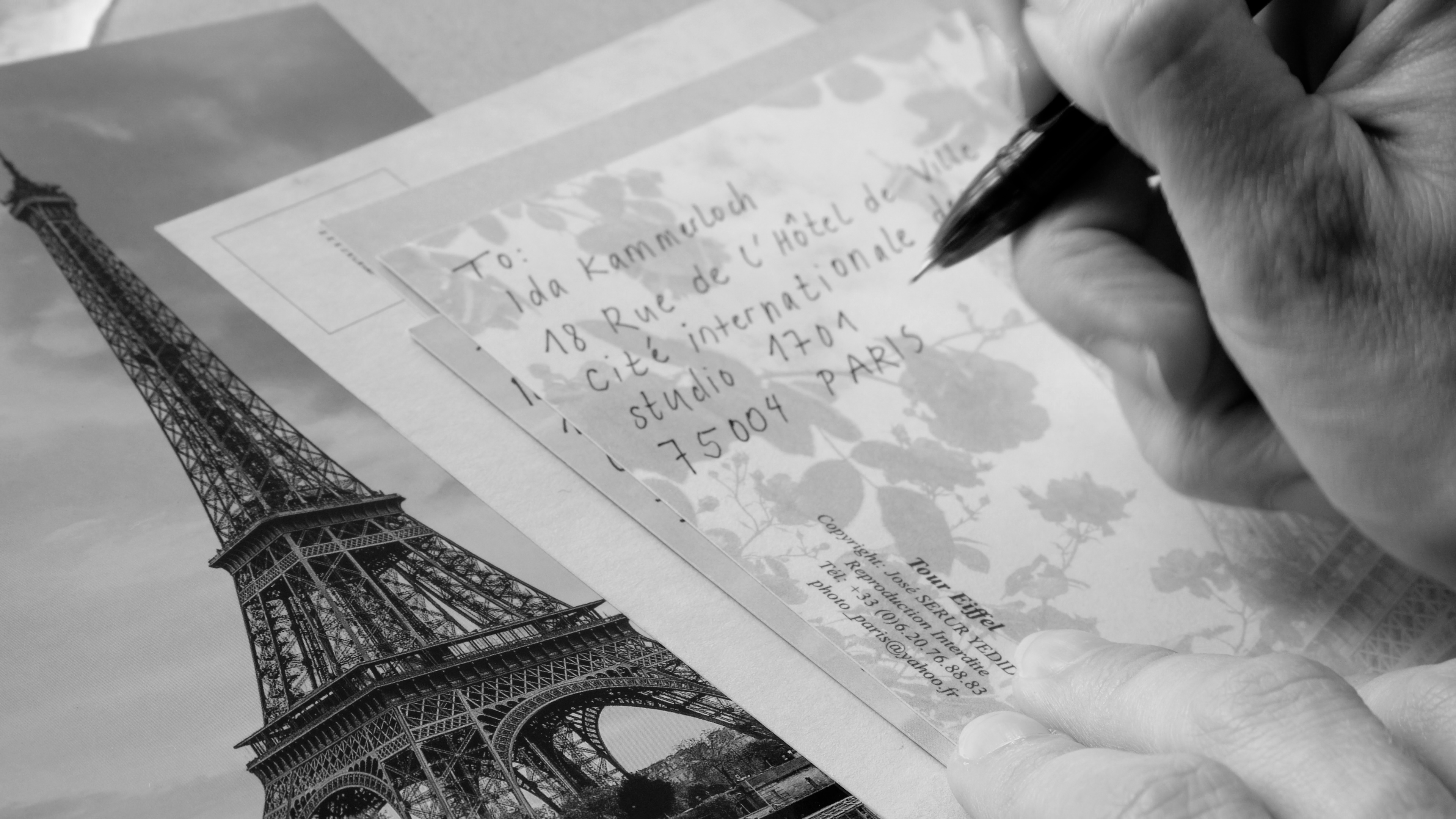

The Eiffel Tower stands as a paradoxical symbol: both a singular, iconic monument and a globally replicated image. As one of the most reproduced structures in the world, it has been endlessly tokenized into keychains, postcards, and souvenirs—objects that allow anyone to “possess” a piece of Paris without ever setting foot in France. This transformation from an architectural marvel to a commodified trinket speaks to the tower’s unique ability to transcend its physical location, becoming a universal emblem of romance, culture, and travel. But what happens when this image, stripped from its original context, is reproduced somewhere else—scaled down into a trinket or scaled up into a towering replica? Does it still carry the same weight, or does its meaning distort in the process?

Yet, the journey of these Eiffel Tower souvenirs often reveals unexpected layers of complexity. These quintessentially “Parisian” souvenirs are often made not in France, but in China, primarily in factories near Yiwu—a global hub for mass production and the world’s largest wholesale market for small commodities. Here, the Eiffel Tower’s image becomes this commodity, manufactured for the last 30 years at scales and speeds that redefine its original symbolism. This globalized cycle of production and consumption turns the tower into an object both universal and strangely placeless: a keepsake of Paris, crafted far from its cobblestone streets.

In Tianducheng (Hangzhou), a Chinese city just a short train drive from Yiwu, the Eiffel Tower appears again—this time as a 108-meter replica standing at the center of a surreal urban landscape. Known for Chinas phenomenon of „duplitecture,“ Tianducheng mimics Paris itself, complete with Haussmannian-style buildings, fountains, and wide boulevards. Here, the replica exists not as a souvenir but as a monumental act of imitation, a city concept. Yet, when you stand in front of it, questions arise: Can a copy ever truly mirror the original, or does its new context redefine its meaning? Is the replica a symbol of reverence for Paris, or a display of China’s ability to replicate—and perhaps surpass—the icons of the West?

My project, delves into these very questions. While my residency in Paris was meant to explore the city, my research took an ironic turn. Instead of staying in the city of lights, I traveled for some time to Tianducheng, to explore the source of the Eiffel Tower keychains and encounter the replica firsthand. Staying in a hotel with an exclusive view of Tianducheng’s Eiffel Tower, I began to unravel the story of how this iconic image, born in Paris, has taken on a second life in China.

Is a souvenir sometimes a fragment of a place that doesn’t truly exist—a memory pieced together from scattered impressions? And what happens when the souvenir becomes the destination?

The title of the film is inspired by a documentary my grandfather shot about Paris in just one day.“Études of Paris” was filmed by my grandfather, Vladimir Alin, in 1995 and later aired on Russian television in 1998. During a visit to us in Germany, he took a bus trip to explore Paris for the first time. His film captures the city’s most iconic landmarks and is set to classic French chansons, evoking a sense of nostalgia and tapping into widely recognized cultural imagery.

The film reflects on how cultural icons like the Eiffel Tower are constantly redefined—not just by their creators, but by the global forces that reproduce, reinterpret, and commodify them. In this process, even a perfect copy can take on a life of its own, becoming both a reflection of the original and a symbol of the shifting lines between culture, identity, and power.